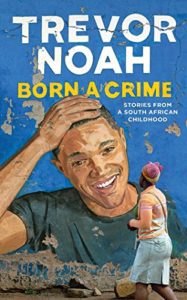

Born a Crime – Book Review

Click ‘play’ to hear me read this post.

A friend whose work I respect recently directed my attention towards Trevor Noah. I watched a few clips of The Daily [Social Distancing] Show on YouTube, triggering the algorithm to suggest other clips, which meant that I watched a few more. When I expressed to this friend how much I appreciated Trevor’s commentary—though I do find the jokes a bit overly-written, and maybe intended for a generation a decade younger than me—she asked if I had read or listened to his book, Born a Crime. I had it on my list, but her inquiry had me move it to the top of my queue.

This is one of those books where, because the audio version is read by the author, and the author is a comedic performer, I have to posit that it’s truly the optimal mode for consumption.

There are some authors where, if you’ve listened to any of their books, or heard enough of their interviews, you can “hear” their voice when you read their books in print. In this case though, to have missed out on Trevor’s many voices, accents, and languages would be a real loss.

Among other things I loved about this book: it was highly entertaining. It seems like it’s only about 1 out of every 10 or 15 books that captures my attention such that I plow through it in a matter of days. This was one of them. I felt giddy when I woke up in the morning and knew I had a time slot that day to delve deeper into the story.

I found it relevant in my efforts to educate myself about racism, to learn about the dynamics of it through a different cultural lens. The realities of racism are depressing, and leaning in to study them can sometimes leave me feeling disheartened. This book felt like a way that I could stay engaged, learn, and remain hopeful—even be entertained along the way. I know, I know—studying racism isn’t about being entertained.

And this is the question I imagine so many of us are now asking: how can I contribute to the cause without becoming so depressed that I burn out and limit the range of my

contributions? Or, said differently: what level of self-sacrifice of my own comfort and pleasure actually serves in achieving collective justice and freedom? I tend to have a pretty harsh inner-critic when it comes to spending my free time not actively working to dismantle racism. But any activist’s effort has to be sustainable in order to cross the finish line, right? I found Born A Crime to be a great bridge between assuaging burn-out and staying tangentially connected to the cause.

Here are two excerpts from the book I found most impactful:

- “I often meet people in the West who insist that the Holocaust was the worst atrocity in human history, without question. Yes, it was horrific. But I often wonder, with African atrocities like in the Congo, how horrific were they? The thing Africans don’t have that Jewish people do have is documentation. The Nazis kept meticulous records, took pictures, made films. And that’s really what it comes down to. Holocaust victims count because Hitler counted them. (emphasis mine) Six million people killed. We can all look at that number and rightly be horrified. But when you read through the history of atrocities against Africans, there are no numbers, only guesses. It’s harder to be horrified by a guess. When Portugal and Belgium were plundering Angola and the Congo, they weren’t counting the black people they slaughtered. How many black people died harvesting rubber in the Congo? In the gold and diamond mines of the Transvaal?” (Chapter 15)

As a Jewish person, I was really struck by this. On the one hand, grief is grief—I don’t think we should compare how bad one genocide is to another based on the casualty count. On the other hand—for better or for worse—sometimes it’s the scale of an atrocity that gets us to the point of critical mass to take action.

2.“Nelson Mandela once said, ‘If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.’ He was so right. When you make the effort to speak someone else’s language, even if it’s just basic phrases here and there, you are saying to them, “I understand that you have a culture and identity that exists beyond me. I see you as a human being.” (Chapter 17)

When I check my understanding of something a client has shared with me, sometimes I try and repeat back exactly what they’ve said. Other times I paraphrase, in an effort to balance joining with them, while also offering an expanded perspective within the nuance of augmented language. Ideally we have enough rapport that if my paraphrase is off the mark, they correct me, and we can land linguistically in a place that leaves us both feeling heart-connected.

Trevor shares in great detail various experiences he had of being spanked or hit by his mother and step-father. I am so immersed in studying trauma that it’s difficult to see

through any other lens. Many of my studies have pointed to the grave impacts of ACEs—Adverse Childhood Experiences—including, but not limited to, increased probability of cancer.

Anytime I hear about the ACEs study, I often find myself in a daze, thinking, Man, there really are no happy endings. This is in contrast to what Peter Levine says about healing trauma, that “this journey has a finish—a resolution that leaves us richer and fuller for having accomplished it.” (Levine, p. 153) So although the future is left untold (as we don’t know how Trevor’s long-term health will pan out), suffice it to say that for the time being, all criticisms of capitalism aside, he made it!

Lastly, it was fun to travel down memory l

ane toward my own upbringing through Trevor’s adolescent entrepreneurial pursuits, namely: burning mp3 CDs and selling them at school.

Perhaps needless to say: 5 stars, I recommend this book.